How did Google's illegal ad monopoly work?

I dug through the ruling that declares Google an illegal monopoly. I explain the ad market and outline the ways the court accuses them of acting anticompetitively.

Last week, Google was found to be operating an illegal monopoly in the ad tech space. I highly recommend reading the ruling if you want to understand the case. It provides a great description of how modern adtech stacks work, and how Google abused them unfairly. You probably need a few hours to fully absorb it.

You don’t have a few hours? You’ve come to the right place. I don’t have any qualifications — I’m not a lawyer and I never worked in adtech. But unlike many of you, I read the ruling and I’m doing my best to summarize it. If you want something authoritative, then find someone who knows what they’re talking about.

Anyways, here are my notes:

Google was accused of having an illegal monopoly in three parts of the adtech stack: publisher ad servers, buy-side ad exchanges, and advertiser-side ad networks like Adwords. The entire complaint focuses heavily on their abuse of the buy-side ad server and exchanges, saying that they were able to unfairly exclude other exchanges from competing because of anticompetitive features in the publisher ad server.

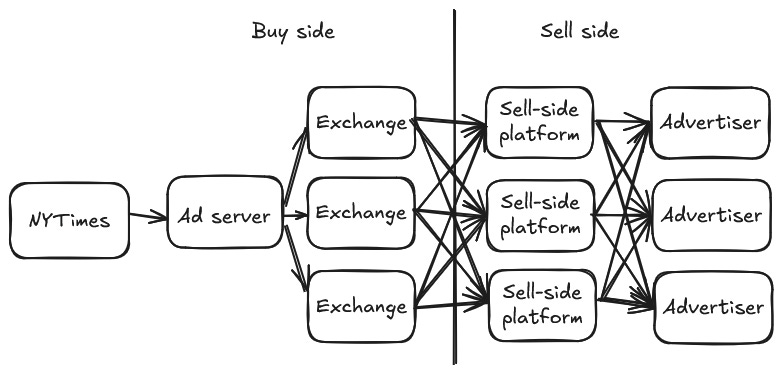

To describe the adtech stack, imagine that a publisher like New York Times wants to run advertisements. Their view of the ecosystem might look something like this:

The NYTimes contacts an ad server (run by Google) that fires off a query when someone visits the page. The ad server contacts competing exchanges (one of which is owned by Google) to determine which exchange can provide the best bid. Each exchange itself runs an auction across all of the sell-side platforms to determine what to bid for the given request.

The NYTimes’ ad server is supposed to make decisions that are in the best interest of the New York Times. Otherwise, why would they use it? However, Google repeatedly takes advantage of the fact that they have a monopoly on ad servers AND also runs its own exchange. They give their own ad exchange preferential treatment over competing exchanges, deliberately harming the competing exchanges.

Google added features across the publisher platform / ad exchange ecosystem to limit competition.

First look: any publisher using Google’s publisher platform was required to offer Google’s exchange a buyout price. So Google’s ad exchange could buy inventory even though another ad exchange might have bid higher.

Open Bidding: to counteract Google’s stranglehold on the market, publishers began a practice called “header bidding” where they could offer the inventory across many ad exchanges simultaneously. Google added Open Bidding as an implementation to their own ad platform so that publishers could easily use the Google-provided header bidding instead of rolling their own. However, there was a big difference: when it was done on-platform, Google would charge non-Google ad exchanges a 5% fee.

Last look: After the auction ended across the exchange, Google’s ad exchange was allowed to submit a bid 1 cent higher than the winner and steal the auction.

Project Poirot: Google’s publisher platform simply offers non-Google exchanges much lower revenue, causing Google’s ad exchange to receive a significant boost. On average, spending on non-Google ad exchanges dropped 15%.

Unified pricing rules: Worried about anticompetitiveness, Google removed Last Look and introduced “Unified Pricing Rules.1” Some publishers had grown concerned about their reliance on Google. To counter this, they set their Google exchange bids much higher than their non-Google ad bids. In theory, this should have caused the Google exchanges to receive much less traffic. Unified Pricing Rules forced their Google ad exchange bids to be the same price as non-Google ad exchanges. Google allowed publishers to set higher prices for non-Google properties.

After all of these changes, many publishers were disgruntled over their reliance on Google’s ad tech stack. They had explicitly tried to break their reliance on Google through “header bidding” that would allow them to contact multiple exchanges. But Google ended up capturing them by moving a Google-friendly header bidding into the publisher ad server. The judgement notes that Google retained 99 of their top 100 publishers because there were no realistic alternatives to Google’s publisher stack.

Google tried to argue that the entire market is a two-sided marketplace. But the ruling notes that across the adtech industry, each of the components are considered to be their own separate lines of business and function as their own marketplaces.

Google’s assertions that there were alternative stacks like Facebook’s or Amazon’s were not compelling because it’s not like the New York Times could exclusively advertise on Facebook or Amazon. They have inventory on their site that they need to fill and Google’s publisher platform is the only viable game in town.

In conclusion: the court agreed with the characterization of their publisher ad server and ad exchange constituted monopolies. Additionally, because of the anticompetitive practices listed above (and some unlisted), they acted illegally and anticompetitively.

When I left Google in 2015 after almost 5 years on the Google Docs team, I asked everyone I knew the following question: “Did Google make money off of me?” I got every answer under the sun.

“Obviously! you helped write features that are checklist items in enterprise contracts.”

“Obviously! the product is mostly free but you are responsible for any downstream revenue it may generate in perpetuity.”

“Obviously not! If Google Docs were a standalone business it would be wildly unprofitable.”

“Obviously not! It’s silly to believe that Docs is the primary reason that anyone buys an enterprise contract over Microsoft.”

But to me, the most correct answer came from an engineer on the Google Sheets team. He said, “They obviously made money on you. It’s incalculably large. You participated in creating an ecosystem between Docs, Chrome, the other editors, and every future integration that Docs has. Strengthening a part of the ecosystem strengthens the whole thing, and causes everything to become more valuable as a unit.2”

The ad money was obviously the secret sauce to this ecosystem. Nobody pretended that the Docs/Drive organization could stand alone. Microsoft would have killed us before breakfast3. But Docs was granted years and years where the only objective was growth. Nobody cared if the growth was enterprise or consumer. They just wanted growth. Google Docs became huge and eventually the focus shifted towards enterprise customers.

It also enabled lots of bad behavior across the company. In truth, the ad money erased all of the risk. There was no consequence for the management chain lacking vision. There was no consequence to being an also-ran in a new industry. Many of the engineering “best practices” that I learned only make sense when money and delivery timelines don’t matter.

If you haven’t worked in tech for long, anytime a company removes a controversial thing and adds a new thing in the same breath, that new thing is somehow worse.

Yes, I did believe the take that maximized my contribution. No, I will not be taking questions at this time.

Back then, Microsoft’s tactic when competing against Google for a contract was telling the prospective client, “If you choose us, we will give you every feature in Google’s offering for free.” How do you compete with that?